Guide to how to play the game, same as the in-game help

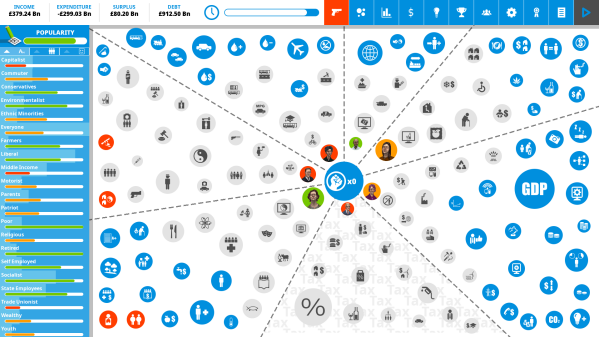

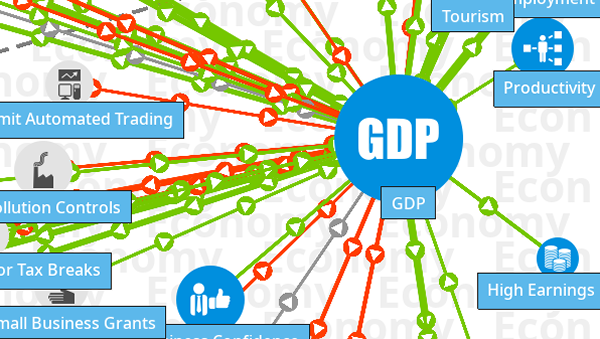

The main interface is iconic in nature. In other words there is no map or 3D world to navigate, just a complex graphic of interconnections between different political and economic aspects of your country. The main principle of understanding the graphical user interface (GUI) is to realise that everything affects everything else. The key to grasping the game is to understand the way in which A influences B which affects C which then comes back to alter A. Politics and economics are complex! You can see how this works by using the mouse to hover the cursor over any icon on the main screen.

This will show a series of lines connecting an item with others. Green lines indicate a positive effect, red a negative effect. The faster the arrows move, the stronger the effect.

Note that positive/negative are not value judgements, they are just numerical. A positive effect on unemployment is generally a BAD thing. A negative effect on pollution is generally a GOOD thing. By following the path of lines connecting items you can trace back the ultimate causes of change within the country. Maybe poorly funded schools lead to poverty, and poverty leads to crime. Increased crime reduces tourism which affects GDP, which in turn increases unemployment, making poverty even worse… and so on.

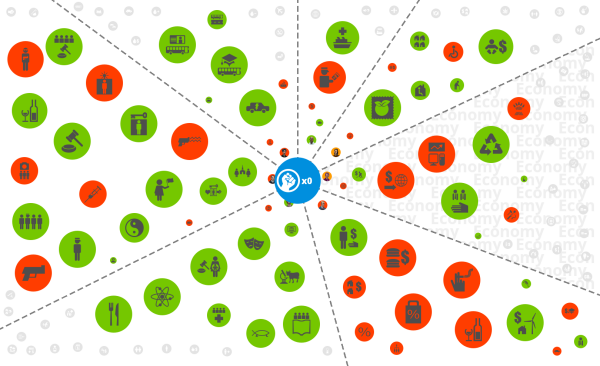

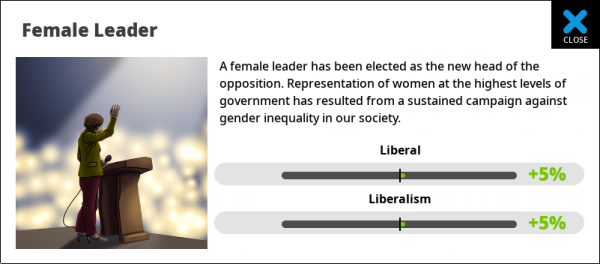

Each voter is defined as either liberal or conservative, and socialist or capitalist and fits into one of the three income groups (low, middle or wealthy). These groups are all special because they exist on a spectrum. Nobody can be a liberal AND a conservative, but they may (for example) be a very moderate liberal.

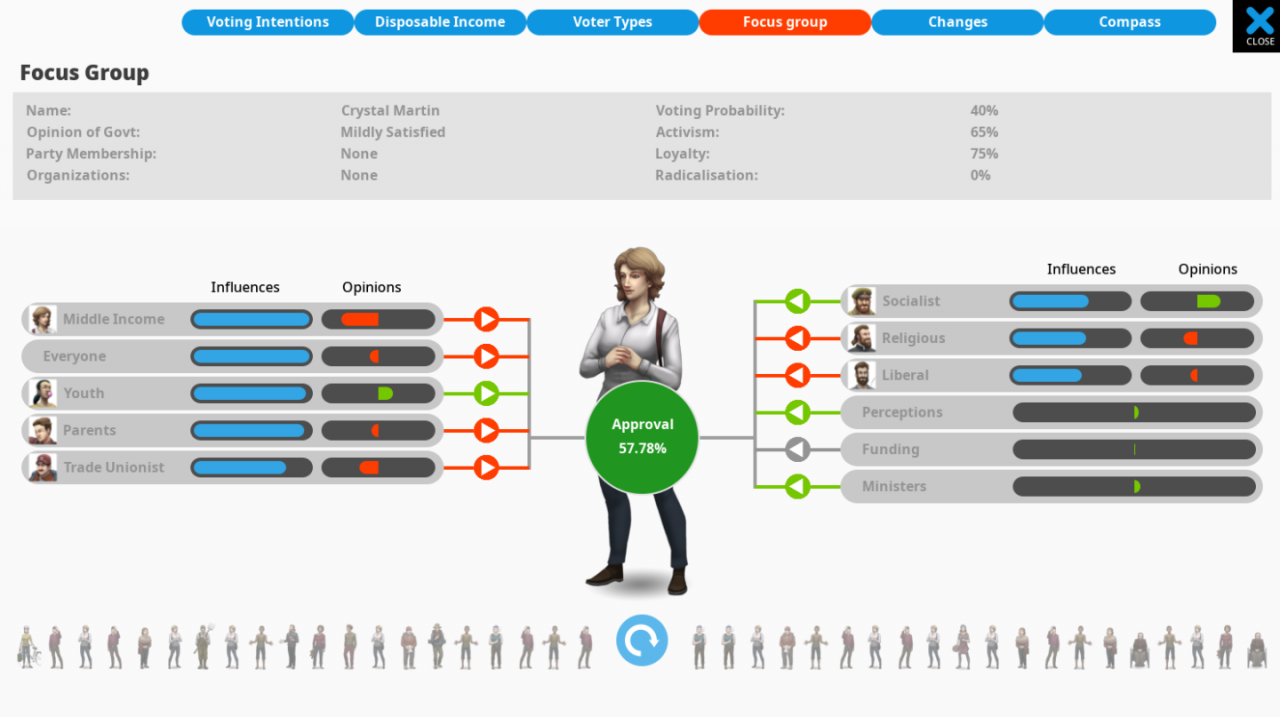

Voters are likely to be members of several groups, and identify with each group to a variable extent. A voter needs to be greater than 50% invested in an issue before they join a group. For example, Crystal is a young adult and has a new-born child. She is a moderate socialist and a moderate liberal. This means she is influenced by different groups to a greater or lesser extent i.e. Crystal is 65% socialist, 96% parent, 63% religious, 80% trade unionist and 97% young etc… Other voters might be more avidly religious and feel more strongly about religious policies. Voters that rarely attend church might be less concerned, or affected by, the same policies. It’s impossible to be young AND retired.

One key concept for voter groups in Democracy 4 is to understand that their happiness is theoretical. In other words, if socialists are 87% happy with the government, this doesn’t mean everyone in that group has that opinion. Socialists can (in theory) make up 100% of the electorate and be 100% happy, and you can get zero votes. How? Because each individual socialist belongs to other voter groups..

They may be unhappy with all of the other aspects of their life (liberalism, motoring, parenthood, patriotism…). In this case they may still vote against you. They might be saying to themselves, ‘As a socialist, I love the current government, but thinking about the bigger picture, I cannot vote for them’. This is a key concept to win over the electorate, it’s not enough to pick a single voter group and make them happy.

Each voter group maintains its own level of cynicism and this acts as a negative effect on how those voters feel about you. Cynicism is caused by making policy changes that appeal to voters just before an election, or that upset them just after an election. It is also caused by ‘flip-flop’ policy changes where a policy is implemented then quickly reversed. Cynicism eventually tails off and is forgotten. Note that it’s per-voter-group, so socialists may be cynical of you, but not other groups. You can view cynicism as an effect on the voter group’s details screen, or see it listed on the polls screen.

As well as cynicism, voter groups also keep track of government complacency. This is a key concept in staying in power. Voters are generally an ungrateful bunch, and take an attitude of ‘what have you done for me lately?’ when it comes to supporting the government. In practice, voter groups who are initially happy will, over time, start to take the policies that please them for granted, and this will show up as complacency on the details screen for that group, and also on the polls screen. If support from that group falls low enough, complacency levels will drop away again. Over progressive terms, the maximum level of perceived complacency will increase, so after each election victory you will face even more accusations complacency from your core supporters, until eventually they may become very difficult to please.

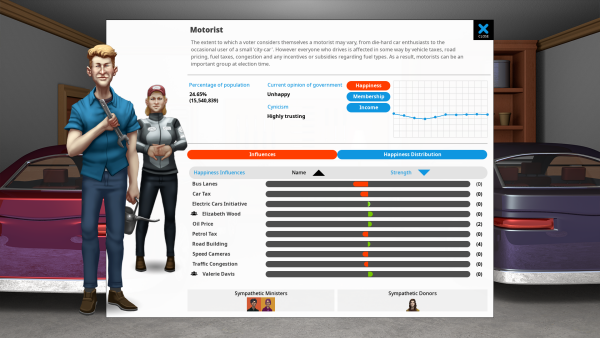

Voters can change membership of groups over time. The extent to which a voter identifies with a group will diminish as a result of policies or events, and eventually when it drops below a certain level they will no longer be a member of that group. For example, if your policies towards motorists are especially negative, those people who were ‘borderline’ motorists will eventually sell their cars. You can view the impact of policies and other factors on group membership on the voter group details screen by clicking the ‘membership’ tab on the graph. This shows the current impact and how it has changed over time.

Focus groups are great for understanding how voters make decisions. You can look at a random cross-section of society in the global focus group on the polls screen. Click on each member of the focus group for information about that voter, as well as the voter groups they belong to (with a bar showing how strongly they identify with each group) and the current affect that membership has on their final decision, shown to the right. Be aware of the fact that how much they like or dislike the government does not necessarily mean they will turn out on election day, unless compulsory voting is in force.

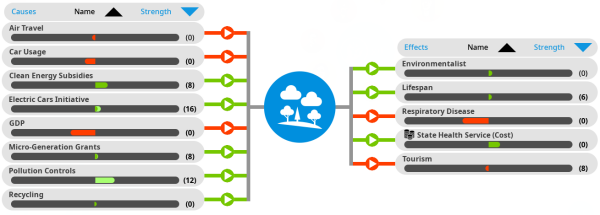

Firstly, cause and effect can be positive or negative (i.e. they can raise the value [this may or may not be desirable] or reduce it). They can also take affect instantly or over time, which Democracy 4 calls ‘inertia’. Effectively, this means the influence that gets applied is not taking the current value of the source object, but the average over a certain number of turns.

A good example is pollution controls and the environment. If you look at this influence as a ’cause’ for the environment, after you have made changes to the policy (Pollution controls) you can see that the effect is gradually moving from its original position to its final position, as shown by a lighter-colored bar. Most effects are actually instant, and have 0 inertia, but some have a huge amount of it. In practice, this means that you need to plan ahead, and also be aware that you are never simply looking at the outcome of your current policy decisions, there will very often be some inertia or ‘lag’ in the effects of your actions.

Policies may have just a few effects, or dozens of them. Initially, some policy effects will be hidden until a situation is triggered and they become apparent.

Policies are split into different areas of government such as ‘transport’ and ‘tax’. These areas are key to understanding the layout of the main screen of the game, as each area is a different zone on the main screen background. All of the data regarding tax is in the tax area, for example, and this includes not just policies, but also statistics and situations. Policy icons are grey in color.

As well as being active or inactive, policies are controlled by an intensity slider. This slider is the strength with which the policy is implemented. For laws, it might represent the severity of the penalty, or the effort put into prosecution. For government spending projects it will represent the amount of coverage and money spent. In many cases, the cost, or income derived from a policy will be strongly linked to the intensity slider. The most obvious example is the tax rate for a tax policy.

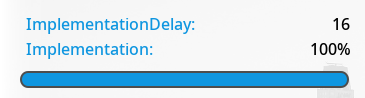

Some policies are technically very simple to implement, such as most new taxes. These can take effect almost immediately. Other policies may take a number of terms to fully implement, such as building new rail infrastructure or a space program. The policy details screen shows the extent to which a new policy has been implemented. Obviously the effects of a policy are scaled to reflect this, although the full cost will have to be paid.

Implementation is important because in many cases you will have to think far in advance when committing to long term policies such as science spending or many education policies. In addition to having an effect on the time to implement a new policy, this implementation delay also affects changes to a policy slider. So for example, if you have a very weak military, and move the slider to the right for full intensity, new tanks and soldiers will not appear overnight. Instead, the slider will gradually move towards its intended position over time, as changes are made.

You can see the final target position of a policy by the slightly transparent ‘ghost’ slider on the policy details screen. If you change your mind, you can edit the position of a slider.

You can keep an eye on the popularity of a policy either from the policy details screen, or by selecting popularity from the main screen to view policies as green or red icons. This figure can be a bit misleading, because it represents people who have a noticeable negative or positive feeling about a policy. In many cases, the majority of voters will not really care one way or the other. In addition, some policies are expected to be unpopular, but they may be necessary to achieve other goals, or to raise government income. For example, the vast majority of taxes are unpopular with almost everybody, except some redistributive or ecological taxes which will please some voters. This does not automatically mean those policies should be cancelled.

The income or cost of a policy is set by the slider for that policy, but there are also many other factors. Each policy is implemented by the minister for that department, and their effectiveness in their role will have some impact. A very poor Chancellor will result in less tax being raised. A very good minister of foreign affairs will be able to keep military costs under control.

n addition, external factors will sometimes directly affect the cost or income of a policy. For example, if you have a state health service, and a problem with infectious disease or asthma, this will push up the cost of this policy. Taxes on certain activities will be affected by their popularity. As a result it is possible (for example) to raise alcohol tax but actually bring in less money, if the tax has the effect of reducing alcohol consumption enough to offset the higher tax rate.

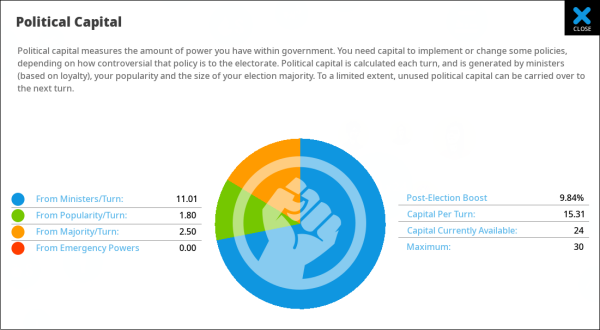

New policies can be implemented whenever you like, but introducing a new policy will cost ‘political capital’. This is a representation of the political effort required to change, cancel or introduce a new policy, and is a measure of the political difficulty associated with an action. Non-controversial policy changes, such as a boost to spending on community policing, may use very little political capital, whereas introducing conscription or the death penalty will require vast amounts. You can see how much political capital you have by clicking the icon in the center of the main screen.

Political capital is generated each turn, based on your popularity, your electoral majority, the loyalty of your ministers, and whether or not emergency powers are in effect in a crisis. You also get a slight boost at the start of a new term. Political capital always seems to be in short supply, so make sure you spend it wisely on the most important policy changes.

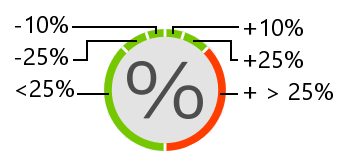

Policy Icons on the main screen have a circular outline with segments that illustrate if a policy slider can currently be increased or decreased, given the amount of political capital available. The amount required is split into segments for +10%, +25% or more in a clockwise direction, and in the anti-clockwise direction for policy reductions. You can turn this off under options.

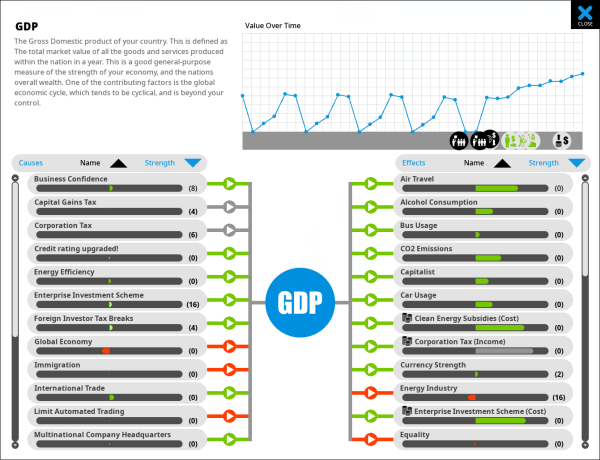

Statistics icons are always blue. These statistics act in some ways like policies, because they too can affects other items. Remember that in Democracy 4, almost anything can affect almost anything. A good example is GDP, which has a vast list of inputs and outputs. It’s affected mostly by policies, and some of the more common effects it has are on the costs of other policies, and the income derived from taxes which depend on economic activity.

Note that you cannot make any changes or have any real impact on statistics directly, all you can do is make policy decisions that hopefully push those statistics in the right direction. Voters are aware of these statistics too. Rising inequality will upset some, and rising unemployment or CO2 emissions will upset others. Statistics are so important that a selection of them is always displayed prominently on your quarterly report.

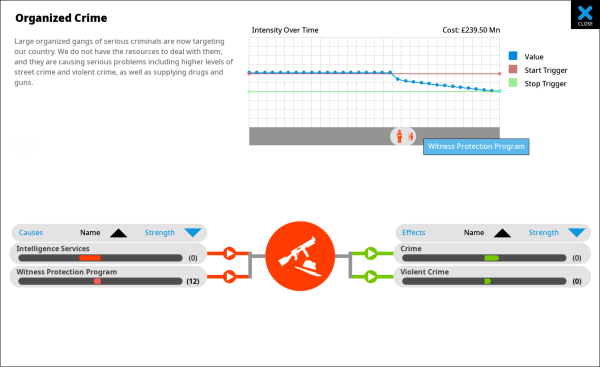

In most cases, situations have a ‘start’ trigger and a ‘stop’ trigger point. In general, this means that it is easier to start a situation than end it. For example, if your policies have led to race riots, then stopping the riots will require a much stronger policy response than would have been required to just prevent them starting in the first place. This is because situations have momentum.

In general, it’s a good bet to think about potential bad side effects of policies *before* a bad situation develops. Note that situations can affect other situations too, potentially leading to a general downturn in the country.

Events are one-off occurrences that generally have short term effects, but if those effects are negative and badly timed (just before an election, for example), they can be devastating. You hear about events on the quarterly report screen, and they are not shown anywhere else, although you may see the lingering impact of events as effects on any of the other screens in the game. Those effects usually die out gradually over time. Be aware that not all events are bad. Some are a reflection of good economic policy, or wide-spread provision of social services or prosperity.

Each option may have a variety of short and long term effects on voters, statistics, situations and so-on. You are not able to proceed to the next turn until outstanding dilemmas have been dealt with. There is no other place where you will see the dilemmas, although you may be able to see the effects of your decisions as inputs to items on their various details screens.

Elections can be tense because they are one of only two ways you can lose the game (the other by being assassinated). Once an election is over, you can see what percentage of each voter group turned out to vote, and what percentage of voters cast their vote for you.

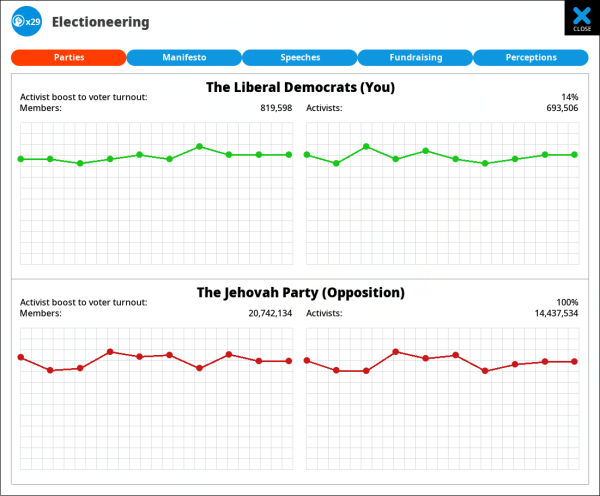

There are either two or three parties in Democracy 4, depending on the country. You can choose a party name at the start, or you can type in your own name. You can also choose the name of your opponent, although this has no impact on them. Democracy 4 is not concerned with the policies or views of the opposition, who are assumed to oppose everything that you do. If a voter is happy with you, they vote for you. If they are not happy with you, they vote for the opposition.

As well as being a target for votes, parties are also represented within the game. Each voter can be a non-party member or a party member. Party members may or may not be activists. Most people do not join either party. If they become very happy with your government, over time they may decide to join your party. All this really means is that they are guaranteed to turn out and vote on Election Day, regardless of how strongly they feel. They are also guaranteed to vote for you. If they become even happier with your government, they may over time sign up as an activist. If voters view you negatively they may join the opposition party. You can see the values for members and activists on the party screen. You can launch this screen from the rosette button near the top right of the main screen.

Activists are special because they proactively go out and post leaflets, wear badges and put up signs. This has no effect on how people feel about your government at all, but it *can* boost turnout during the election. In close elections, the final victory may go to the party that boosts turnout the most. In countries where voting is compulsory, this is never an issue.

Turnout is also affected by strength of feeling. Voters who are happy will turn out on election day and vote for you. Voters who are very unhappy will turn out to try and kick you out, but voters in the middle with no strong feelings either way are likely to just not bother. This is political apathy, and is slightly different for each country (based on real-world voter turnout). You can adjust voter apathy to increase or decrease base voter turnout from the customize game screen before you start. In general, you will find that a middle-of-the-road compromise government will result in low turnout, and a hard-liner transformative and divisive government will result in very high turnout.

All terrorist groups draw their support from the membership of existing pressure groups and organizations. For example, if government policy particularly upsets patriots, some of them may join a patriotic pressure group to vent their anger at the government. If the anti-patriot policies persist, particularly angry members of those groups may, over time, become ‘radicalized’ enough to join a dangerous terrorist organization. At this point, their growing membership will pose a serious threat to you, although you are likely to be warned of a plot before any serious attack.

The attacks may or may not succeed depending partly upon luck and partly upon the defensive mechanisms of the state such as wiretapping and intelligence services. Note that the process of radicalization varies with the temperament of the individual and the group involved. It is also a reversible process, although this will take time.

There is also an extent to which placating and pleasing the basic voter group from whom terrorists are drawn will reduce the probability of attack, so if you have a large and dangerous group of religious terrorists, you can reduce an imminent threat by changing policies to please the religious voter group. Also, note that terrorists are actual voters drawn from voter groups, so reducing the number of socialists will reduce the pool of potential recruits to both socialist pressure groups and socialist terrorist organizations.

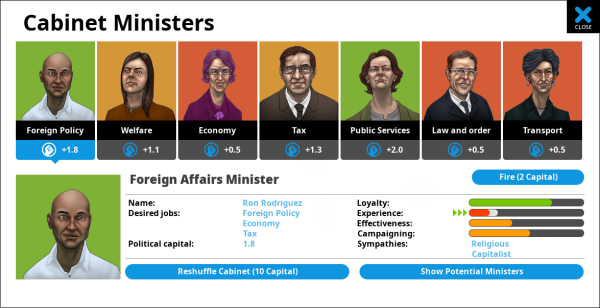

Ministers generate political capital each turn. Some of them are more influential and powerful than others, and thus will generate a larger amount. This enables you to get more legislation passed. The amount of capital they generate is dependent upon their loyalty. A minister’s loyalty may go up or down over time, depending how you run the government. There is also a general inevitable downward trend of loyalty as a minister becomes more jaded and cynical with the government. It’s best to replace people before they get too disloyal. Ministers can resign, (although rarely without warning) and resignations are unpopular.

Ministers also have a rate of ‘effectiveness’. This is essentially a measure of how good they are at their job. The longer they stay in cabinet, the more experienced and effective they become. Effectiveness is also determined by their natural disposition towards certain jobs. Each minister has a few jobs they would especially like, and these are the ones in which they would be most effective. The effectiveness of a minister is important because it determines the cost of (or income from) policies. It also affects the implementation rate or change-rate of existing policies. Simply put, an experienced and effective minister in the right job will get more done for less, and faster.

Ministers are not any different from voters, in that they have certain allegiances and attributes. Because of this, they will appeal to, and identify with, specific sets of voters who they are described as having ‘sympathy’ with. This is an effect that cuts both ways. For example, a specific minister may be a commuters champion and very religious. Having them in government will please both of these voter groups, regardless of policies, because they see ‘someone like them’ in government, and feel that they must be acting in their best interests. Obviously this is a good thing, if you need support from those groups.

On the other hand, A minister’s happiness is directly affected by the happiness of those sympathetic voter groups. So, in our example, a government that angers commuters and religious people is going to upset the minister, which will reduce his or her loyalty. The minister will work less effectively to implement your policy decisions, or support you in introducing new policies. Because of this two-way effect, you may find selecting a minister to fill a vacant post a tricky business.

From time to time ministers resign, which is bad for the government, but you can fire and hire replacements whenever you wish. Remember that experienced ministers are more effective so be careful. If you want to move ministers around without firing them (fired ministers are gone for good), you can call a reshuffle, which has none of the bad PR effects of mass firings.

The moment there is a change in your country’s credit rating, there will be a noticeable change in interest rates. This can escalate very quickly and suddenly so it is worth keeping an eye on. One of the key factors used by the market to determine your credit rating is your debt to GDP ratio. If your economy is doing well and your GDP is high, this will keep interest rates low and you can get away with a higher level of debt than if GDP is low.

When in a coalition, you will sometimes get offered a deal by your coalition partner, where they ask you to implement one of their policies, in exchange for more political capital. It’s entirely up to you if you take that deal, but be aware that the electorate will hold you responsible for all your actions, even if it was a coalition partner’s idea.

Speeches and manifesto pledges can only be made very shortly before an election takes place. Manifesto pledges are effectively free promises, but failing to keep them if you are re-elected can prove unpopular the next time you ask for peoples’ votes. Speeches are a way to trade-off support from one group of voters to another, depending how important they are to your campaign.

The fundraising screen shows you how much money your party has raised for the election, compared to other parties. Money comes from individual member’s donations, plus some large donations from wealthy individuals. The wealthy donors will have their own ideas concerning policy, and you may occasionally be asked to implement policies in exchange for their continued support

The amount of money you have at the election will be a factor in determining how well your campaign goes, and how likely your supporters are to actually turn out and vote. The campaigning skill of each of your ministers will also have an impact. It might make sense to replace disloyal ministers for ones who are better at campaigning as you get close to an election.

As well as your policies, voters form opinions on you based on their perceptions of your personality. You can improve their perceptions by taking part in media events that are designed to change the way the voters see you. This can be an easy way to get support, but carries risks. Some media events can backfire and have the opposite effect, actually reducing your chances of re-election.